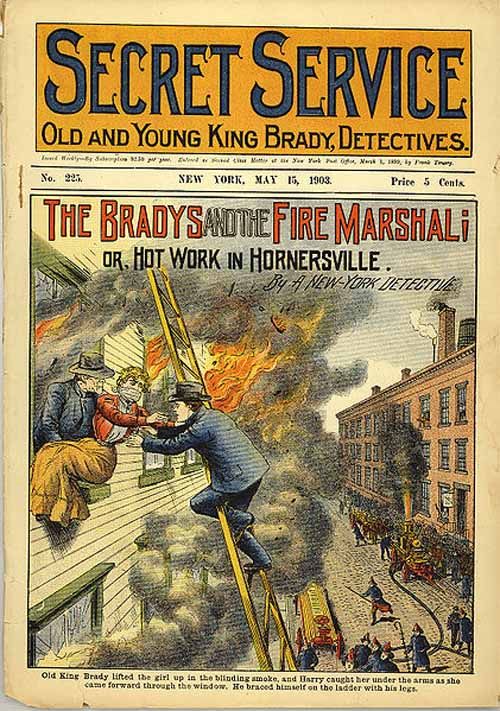

Dime novels in America began to appear around the early 1860s, and their cheap, booklet-like composition made the act of owning books more accessible to a broader range of people. At a cost of 5–15¢ each, reading wasn’t just for the aristocracy anymore. The price helped the books into the hands of the working class; before this, regular books sold for $1–1.50, which was completely unaffordable for them. Their pages were filled with formulaic-if-enthralling tales of rollicking adventures. Their short length — the books were printed on cheap, lightweight paper — helped to get them into people’s hands (and back pockets). In the beginning, they were especially popular with bored Civil War soldiers, many of whom read the books during mundane moments at camp.

The Early History of Dime Novels

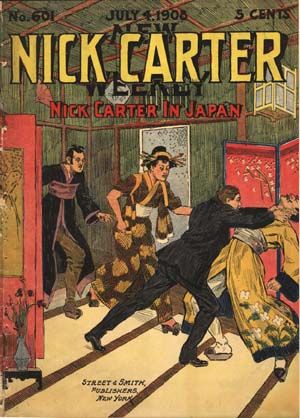

According to Pamela Bedore, author of Dime Novels and the Roots of American Detective Fiction, 50,000 dime novels were published between 1860 and 1915. The first publishing house of the genre was run by Robert Adams and Irwin and Erastus Beadle, and their first title was Ann S. Stephens’s Malaeska, the Indian Wife of the White Hunter. Previously published in a magazine, Beadle and Adams got it for cheap and paired it with dramatic illustrations. This would be the first book of many and, over time, Beadle and Adams standardized the printing process, making it cheaper to mass produce novels. Many of the earliest dime novels focused on Native Americans, and then stories moved on to feature cowboys, bandits, and train robbers. The books’ titles were dramatic and attention grabbing, such as Fred Fearnot’s Revenge, or Defeating a Congressman. The writing in these texts is plain, not wordy or filled with character analysis and development, but still evocative enough to draw the reader into the story. For newly literate working class Americans, the simplicity made for an enjoyable entry point into reading. Unfortunately, Adams and the Beadle brothers had a big ol’ fight at some point, and Irwin Beadle left to start his own company with bookkeeper George Munro. Together, they founded a publishing house named Munro, and then began to print their own “Ten Cent Novels” — see what they did there with the name? Francis Scott Street and Francis Shubael Smith founded Street & Smith in 1855. It was an especially prolific publishing house that maintained strict regulations for their books — dictating plots, characters, and conventions to authors. They didn’t allow for much creativity, but the money was good and so many wannabe authors were interested in it as a side-hustle.

Dime Novel Authors

Colonel Prentiss Ingraham was one of the most prolific of the genre’s authors, writing plays, poems, and over 600 novels. “It is said that one his dime novel stories was written on rush order, the completed work containing 40,000 words on only 24 hours’ notice, without a typewriter” (The Historical Association). Also, author Frederic Marmaduke Van Rensselaer Dey, the creator of detective character Nick Carter, was “rumoured to put out 25,000 words every week for almost twenty years, using multiple pen names.” Look, I don’t know if that’s true, but I sometimes take three hours to write a single page, so either way I’m impressed. The typewriter, invented in 1868 by Christopher Latham Sholes, sped the writing process up immensely. Also, the industry now paid well, and that drew famous authors to the easy money. Some, like Jack London, wrote under pen names. But Louisa May Alcott, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson were some of the well-known names who contributed to Street & Smith’s oeuvre.

The Cheap Book Boom

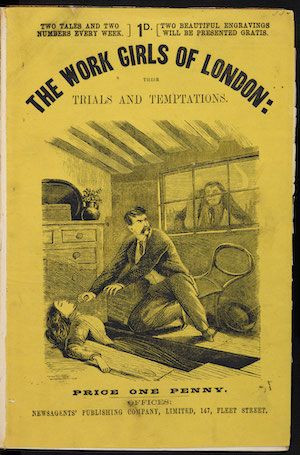

In England, readers devoured ‘penny dreadfuls’. First published in the 1830s and initially known by the more-provocative name ‘penny bloods’, they were gothic fiction tales about pirates and highwaymen. The books came out on a weekly basis and sold like hot cakes, providing lurid stories alongside haunting illustrations. As with dime novels, the novel’s content shifted — moving from Victorian gothic tales to mystery novels and true crime stories. Then, in the 1860s, shifting readership changed the focus of the stories toward children. Back in the U.S., from 1870 onwards, a sub-genre of women’s fiction arose. Mostly, these were romances and murder mysteries. According to The American Women’s Dime Novel Project, “women’s books were the first ‘bestsellers’ in America”. Author Fanny Fern sold 70,000 copies of her book Fern Leaves; another, Ruth Hall, sold over 50,000 copies in the first eight months of its publication. Previously, it was impressive to sell 2,000 copies, so these sales were blowing the roof off that expectation. Dime novel romances always followed a similar course. In each one, a young woman would deal with common plot devices (affairs, lovers torn apart, unhappy marriages). Like the adventure-focused stories, these avoided character analysis and emphasized action. A happy ending was usually provided. And dime novels weren’t the only options for enthralling reading. Readers inhaled the weekly ‘story papers’. They were eight pages long, far less controversial, and made from a combination of text and illustrations (specifically, wood engravings). Their family-friendly vibe made them more publicly acceptable.

Dime Novels: Controversial Literature

The middle class did not like how popular these books had become. Anthony Comstock, a post office inspector and the Secretary and Chief Special Agent for the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, was famous for his disdain. Comstock published the book Traps for the Young in 1883, writing that the books were “literary poison” that would corrupt the youth with “evil reading”. A big problem for Comstock and his ilk was the way that these books recounted crimes, used unsophisticated language, and portrayed women actively going after jobs and relationships. The usual concerns about youth and purity followed, but those did not defeat the popularity of dime novels. Crime and vice did not go unpunished in these novels — in fact, their stories were a celebration of restoring virtue. Arrest the criminals, restore the women’s virtue, yay, the end. However, these stories about wild men and women countered the ordered direction society was going. Celebrating foul-mouthed bandits and cowboys was therefore disruptive to the society’s desire to grow up and get fancy. Some concealed their interest in dime novel fiction, as in a 1922 New Republic article that begins, “Who of that youthful generation who read Dime Novels stealthily and by night, with expense of spirit and waste of shame, imagined that he would one day review his sins by broad daylight in the exhibition room of the New York Public Library?” They were even banned at one point — “burnt so freely as literary garbage”. The New Republic editorial definitely sounds uneasy about the topic, referring to the genre as a “little ill-fitted sister of the American novel”. Research libraries did not organize and catalogue them until after they’d gone out of print. While dime novels still don’t get the respect that they deserve, without them there wouldn’t be many forms of genre writing, including pulp fiction, romance, or detective and crime fiction. Their flawed, influential stories were crucial in putting books into the hands of people who would otherwise have stayed away. We shouldn’t underestimate how important that is, and the history of dime novels should be just as well known as that of pulp fiction or sci-fi. If you want to learn more, read Bedore’s book, or check out The American Women’s Dime Novel Project and the Historical Association.