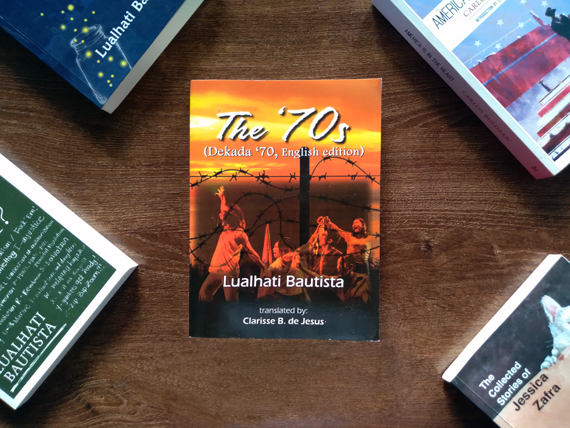

In fact, as we’ve entered the so-called “Asian century,” Philippine literature is finally getting recognized worldwide. There used to be a dearth of Filipino writers in the international book scene. But now more and more writers from the Philippines, from Rin Chupeco and Gina Apostol to Gail Villanueva and F.H. Batacan, are finding representation in mainstream publishing. Earlier this year, Penguin Classics offered Lualhati Bautista, a Manila-based Filipina writer, publication for her book Dekada ’70. In an email by Elda Rotor, vice president of Penguin Classics, she described Dekada ’70 as “very moving, timely, and propulsive” and saw its potential for a wider English-language audience — especially students — outside the Philippines. Aside from that, Rotor was also “intrigued by the work and its impact and study in Philippine classrooms.” If they ink a deal, Bautista will be the first Filipina to be published by Penguin Classics. Publishing someone like Bautista, who mainly writes in Filipino, a language that is largely spoken by the citizens of the Philippines and its diaspora, doesn’t happen every day. And this news definitely arouses a lot of interest. But who is Lualhati Bautista, and why does her book matter to a global audience? Born on December 2, 1945, in Tondo, Manila, Bautista is an award-winning Filipina writer who penned Philippine modern classics such as Dekada ’70, Desaparesidos, ’GAPÔ, and Bata, Bata…Pa’no Ka Ginawa? among others. Dekada ’70, one of her most important works, is required reading in Philippine high schools. The majority of her books are political in nature as she is a staunch activist. In fact, she heavily wrote about the Martial Law in the Philippines, a period in which the then-President and dictator Ferdinand Marcos imprisoned, tortured, and killed thousands. The book is set in that bloody and murderous regime in Philippine history. It follows the Bartolome family, which consists of Amanda, Julian, and their five children. Through the varying life experiences of their children — one is a rebel who gets jailed and another one ends up dead — Amanda sees how brutal and deadly the Marcos era was. Thanks to its success: Dekada ’70 was also adapted into film in 2003, starring local A-list actors. Although the premise heavily revolves around local politics, the themes are universal and can be relevant internationally, especially as authoritarian powers are on the rise lately. Seeing a family living within a ruthless dictatorship and fighting for civil rights would resonate well with international readers. Throughout the decades, Bautista published more radical and thought-provoking tours de force. She wrote more on the Martial Law and on freedom, feminism, and social justice. In Bata, Bata…Pa’no Ka Ginawa?, another one of her most-read works, she challenges the traditional gender roles of women and advocates for equality. Set in the ’80s in the Philippines during the dictatorial era, it follows Lea Bustamante, a mother and a social worker, and her two children from different men. Since it came out in the ’80s, I find the book progressive since the Philippines was — and still is — an ultraconservative country. In Desaparesidos, which in Spanish means “missing people,” she tells stories of people who were lost because of their activism during the Martial Law period. It follows a woman named Anna, a former member of a rebel group of New People’s Army, who searches for her child. ’GAPÔ, which came out in 1988, looks into America’s exploitation of the Philippines. It’s a scathing commentary on the discrimination of Filipino citizens and the ever-prevalent colonial mentality. For the uninitiated, the United States occupied the Philippines for almost 50 years, starting when Spain sold the country to the U.S. in 1898. In this book, Bautista criticizes the U.S. Navy in Subic Bay, Olonggapo City as there were many U.S. servicemen who took advantage of poor Filipina women in the ’80s. With these works, she has been locally recognized for her contribution in Philippine literature, bagging the highest literary awards in the country. But Bautista, who also writes in Taglish, a portmanteau of Tagalog and English, is less known outside the Philippines. And though Dekada ’70 has been recently translated into English, it seems inaccessible to many beyond the Southeast Asian country. In 2019, Penguin Classics released its Asian American line with a minor disappointment: Not even one was written by a woman. Years before, the well-regarded imprint had also published books by Filipino writers Jose Rizal, José García Villa, and Nick Joaquin, but no one thought of publishing a work by a Filipina. Even Penguin Random House South East Asia, which recently published Filipino Lope K. Santos’ Banaag at Sikat (Radiance and Sunrise) in its own Southeast Asian Classics line, is not without some form of gender inequality. Indeed, Philippine classic literature is overwhelmingly too male. If Penguin Classics ends up publishing Dekada ’70, a book that, at the time it was written, examined the changing roles of women in society and the fight against patriarchy, it would be a boon for diversity locally and internationally. Publishing Dekada ’70 as a Penguin Classic would elevate a woman of color in a category traditionally populated by dead white — and, more recently, Filipino — men. It’s sure to be a major win for women overall and for Filipinas in publishing.