Hosted by Michael Hobbes and Aubrey Gordon, author of the book What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat, Maintenance Phase is biweekly podcast tackles topics on health and wellness. This is a fat positive show, and it seeks to shed light on things that are or once were trendy in weight loss, health, and diet culture. Hobbes and Gordon have incredible chemistry and manage to talk through big, heavy topics without interrupting or undermining each other. In addition to the big topics they delve into — things such as the Presidential Fitness Test, protein as a cure-all, the BMI — one of the recurring features on the show is a deep dive into a celebrity wellness book. Of course, Goop has made an appearance, as has the above-mentioned Lansbury, but so has Ed McMahon and the deep dive into Marianne Williamson is a must-listen for anyone who found themself unable to stop watching the LuLaRich docuseries. I’m not usually one who loves book club–like episodes of podcasts, but it absolutely works for Maintenance Phase, as Hobbes and Gordon do such a fantastic job of going in with an eye toward quackery, toward debunked myths of health and wellness, and, maybe as importantly, with the desire to ridicule diet culture while also offering space for levity among the absurdity. It’d be easy to pull together a roundup of books like Maintenance Phase. We’re finally in an era of fat positive and body positive books, including one by Gordon. But what’s more in the spirit of the podcast than instead a roundup of some of the ridiculous, out of touch, and weird celebrity diet books that exist? Some of these would make for outstanding show fodder, and they make for a great reminder to readers more broadly that just because someone has a platform or is a celebrity, that doesn’t make them knowledgable in any way, shape, or form about health, wellness, diet, or exercise. They are instead a reminder of how pervasive and destructive diet culture is, as well as the trends which inspired generations of poor advice (think: the ways fake sugar were held up as superior to real sugar, for example, or the ways that grapefruit or extremely limited caloric intake were heralded as the “solution” to weight loss). Dieting and health are as individual as we all are, and no matter what “advice” is given, it’s never one-size-fits-all, nor should it be. Our bodies are our own, and we can choose to live in our bodies in whatever way we wish. Diet culture and exercise culture can be toxic, and they’re both deeply representative of the culture and milieu from which they’re developed. This will become apparent quickly with the below titles, but it’s worth emphasizing that if celebrities can make up anything they want related to “health” or “wellness,” so can anyone else, with or without any actual credentials to do so. Remember that even celebrities known for their athleticism or fitness don’t tell the whole truth — you may, as the saying goes, have the same number of hours in a day as Beyoncé, but you likely don’t have access to the same resources, money, and hired help she does. It’ll come as little surprise that these books are primarily by white authors for all of the reasons you’d expect. But perhaps, in this particular case, that’s a sigh of relief.

Celebrity Diet Books For Fans of Maintenance Phase

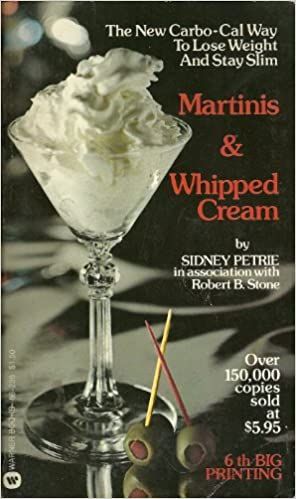

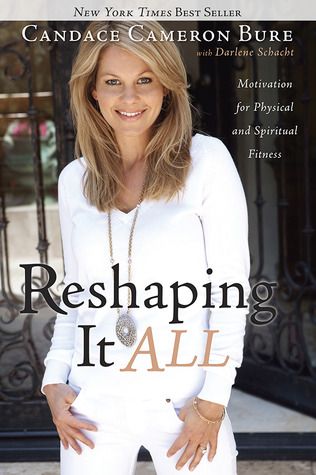

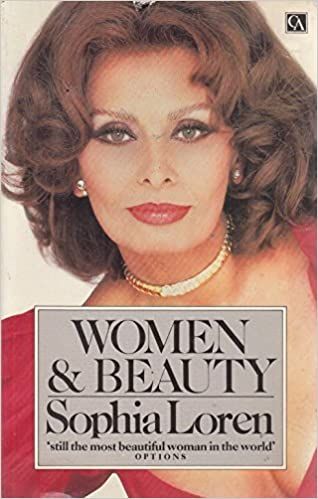

If you’re now unable to stop thinking about diet and wellness books packed with terrible advice, you’ll want to pop on over to a piece by Aubrey Gordon in Self about her own obsession with these books and what they’ve taught her about the culture surrounding diet and wellness. This book is about how she did it, including diet plans that include how to prepare one’s breakfast coffee, and indeed, it leaves plenty of room for the opportunity to “pig out” as necessary. As Maya Sinha describes in a humorous 2020 Saturday Evening Post article, much of the diet advice is a relic of ’80s food culture, and it sounds to me exactly like the kind of book that helped generations of people fall into destructive eating habits (not to mention, 180 pounds is only 10 pounds heavier than what the CDC notes as the average weight for American women). Among the foods to be avoided? Cherries. Prunes. Lentils. Lagerfeld, who lost 90-some pounds in 13 months, was grateful certain soda companies produced diet products since those were a chance for him to “indulge” after giving up his beloved chocolate ice cream. It likely comes as little surprise that Lagerfeld was a white supremacist who demeaned models and other industry folks for being “too fat” during his career. He hated women and immigrants, and it’s not really shocking to see the line between toxicity in diet culture and toxicity in thought more broadly. One chapter in the book details the ways a woman should maintain her physique. Advice included “sexercise,” but more controversially, the “eggs and wine” crash diet. Women were advised to try this for two days and see a quick weight loss: eat 1 egg in any style for breakfast without butter, alongside a glass of white wine; for lunch, two eggs of any style, with two glasses of white wine; and finally, for dinner, 1 steak and the rest of the bottle of white wine. Brown later expanded the diet to incorporate a glass of orange juice. The book notes that there’s not an excuse for being fat and that not only is claiming glandular disorders a cop-out (“Doctors find that behind nearly every fat person lies a history of compulsive, secretive eating”) and that women fresh from childbirth have “proved they can be slim again quick.” But alas, this book offers both diet and exercise advice that isn’t entirely transparent or informed about “Good” and “Bad” food. It was 1991 and the world was afraid of fats, so this particular diet eschewed fat in favor of complex carbs. “Dairy products are not good for us. I weaned myself from whole milk to nonfat milk — if I’m having milk at all. I think cheese is one of the worst things for the body. It doesn’t digest well, and most cheeses are too high in fat and cholesterol,” she writes in the book, also noting that while filming Witches of Eastwick, she participated in binge eating, which she resolved by sustaining herself on microwaved sweet potatoes, baked potatoes, and Caesar salads…which is also not great? Also worth noting here that the cowriter, who is a nutritionist, is a sports nutritionist whose work specializes in high-performing, professional athletes. The advice here isn’t even MEANT for the average person, despite being sold to them. But more than the push for swapping all carbs for as few carbs as possible — and what makes this book noteworthy, even if the author may not be memorable — is this is where the familiar conversions of food to exercise came from. Want to know how many calories it takes to digest certain foods? Indeed, you can find it here. There is a lot of drinking in this book, which is, I guess, great if you like martinis as part of your diet all the time. You can cover the smell of the liquor with your allotted peppermints and chewing gum, though. Bure’s general philosophies are questionable at best (she’s anti-vaccine) and pair that with showing how she herself eats what is a restrictive diet, the rhetoric that most people need to just “try a little harder,” and how she talks about how others should eat puts this squarely in the “nah” box. She’s not a dietician, a doctor, or anywhere in the health world. But one of the quotable lines in this particular title is “everything you see, I owe to spaghetti.” Yes, indeed, this beautiful woman enjoys spaghetti. What’s not mentioned is that comes into play in her monthly 3-day crash diet of 1000 calories. The three days have different meals, but they boil down to very little food in order to achieve that spaghetti excitement. And if you’re hungry, you’re permitted to enjoy snacks of peppers or tomatoes with garlic salt.